This blog is also about listening. So please put on your headphones.

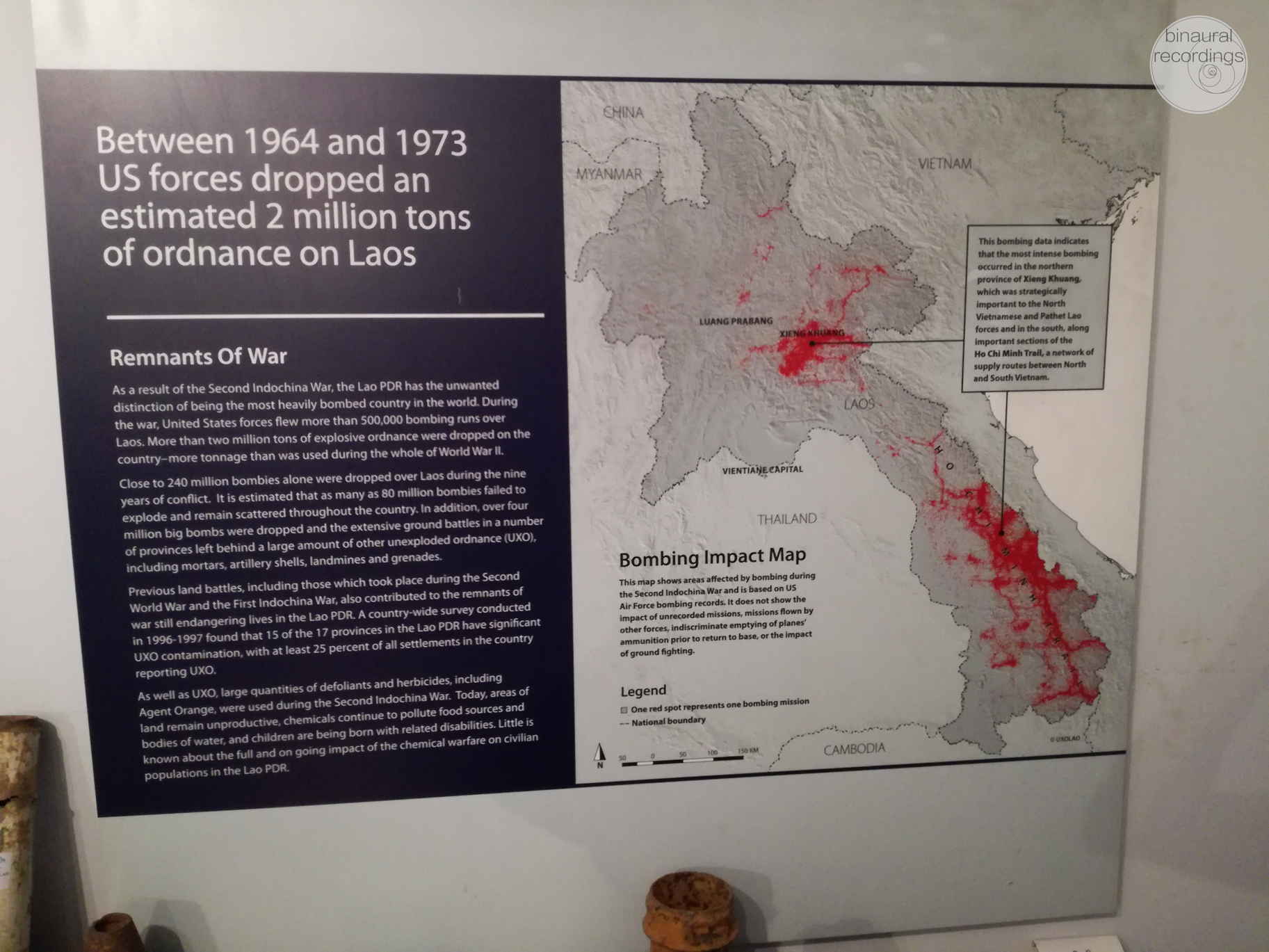

Between 1964 and 1973, the U.S. dropped two million tons of bombs on Laos, nearly equal to the 2.1 million tons of bombs the U.S. dropped on Europe and Asia during all of World War II, making Laos the most heavily bombed country in history relative to the size of its population; The New York Times noted this was “nearly a ton for every person in Laos”. Some 80 million bombs failed to explode and remain scattered throughout the country, rendering vast swathes of land impossible to cultivate and killing or maiming 50 Laotians every year. (Due to the particularly heavy impact of cluster bombs during this war, Laos was a strong advocate of the Convention on Cluster Munitions to ban the weapons, and was host to the First Meeting of States Parties to the convention in November 2010.

source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laos

How everything started

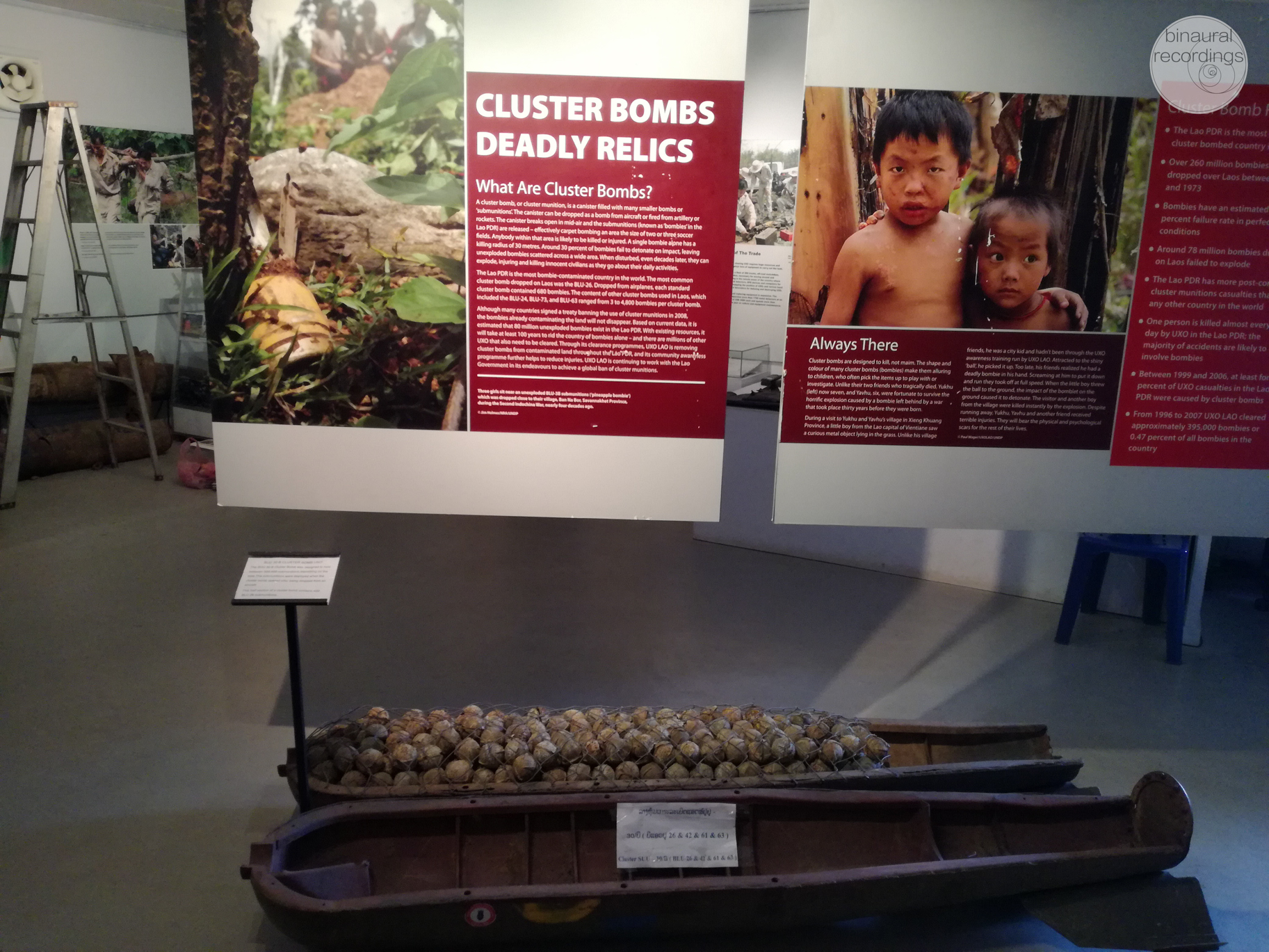

While I was in Luang Prabang I used the opportunity to visit the UXO Lao Visitor Center, a small but excellent exhibit about the bombings, which took place in Laos during the Secret War.

The aftereffects on the country are everywhere visible up to the present day and there are still many areas contaminated with UXO (unexploded ordnance). People get killed and mutilated by exploding UXOs every year.

Of all the different bombs the most inconspicuous but lethal are the “bombies”, little bombs the size of a tennis ball, which were parts of bigger cluster bombs. Cluster bombs exploded over the ground, each of them releasing hundreds of bomblets over wide areas. Up to 30% of the bombies did not detonate upon impact and sunk into the fields or riverbeds where they stay buried until today.

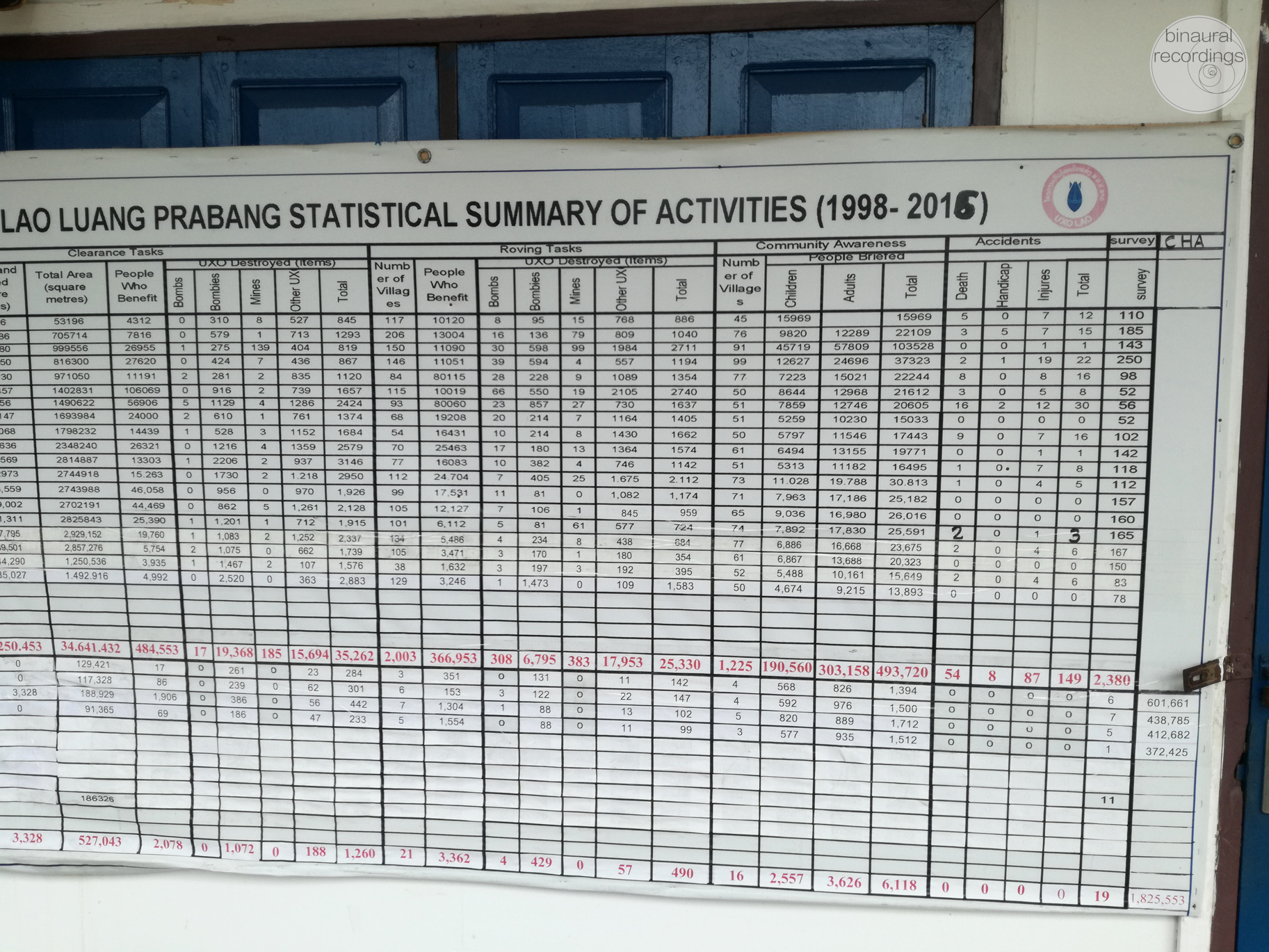

Crews of UXO LAO and MAG have been working hard for more than two decades to clear the land. However, fewer than 1 million of the estimated 80 million cluster munitions, that failed to detonate, have been cleared so far and it is unclear to foresee when or if this country will ever be free of UXO.

The most bombed areas can be found along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a path system hundreds of kilometers long winding through rivers, limestone mountains, and rainforests. it was stretching along the border of Laos and Vietnam and was providing the fighters with supplies in South Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

HOW TO GET THERE

As a was on my way to the popular Thaket Loop on my motorbike, I decided after passing the Nam Theun Plateau, not to proceed towards Thakhek, but to take the opposite direction of Route 12 direction Vietnam and the Mu Gia Pass. I was hoping to track down parts of the legendary Ho Chi Minh Trail. I was thrilled by the idea of entering difficult terrain and challenging my off-road driving skills.

I had saved some GPS coordinates as an orientation guide, found on a blog of a dirt biker the day before, had gathered some information about the area from the official governmental website and felt ready to try my luck.

Route 12 is one of the few existing highways connecting Laos with Vietnam, running on an east-west axis and is heavily used for transportation of goods. Riding along it was a serious matter and required constant vigilance. Heavy oncoming trucks were crossing my lane at high speed according to the only traffic rule in Laos, which is: “the smaller give in” or rather “size matters” and I was forced several times to get off-road to avoid a collision.

The surreal image of cows lying in the middle of the road simply bored and undisturbed by passing trucks a few inches away from them is something which I won’t forget. It seemed also that in the eyes of the lorry drivers the value of a cow was higher than mine, as I was invisible for them.

The more I moved forward the more rural became the area and as I stopped on a village to get gasoline and supplies, the children were running away from me in terror. They acted as though they had faced a demon or never seen a foreigner before. It took up some patience and persistence to convince them to accept the fruits and sweets I got for them.

By evening I arrived at the village Ban Nongchan and found a Guest House, the only one in town with a very good restaurant. I quickly figured that it was a gathering point for truckers.

Truckers seem to be a unique species with the same attitude, no matter in which part of the planet you find them. They tend to be rude, straight forward, show-offs and offer excellent drinking companies. The majority of them were Vietnamese. After their beginning astonishment, foreigners seemed to be a rare sight, their teasing and laughing we had a cool time together, in which I was forced to see pornographic content of their concubines and prostitutes. All of them were married men with families and couldn’t understand why I was solo at my age. After patiently rejecting their offers to get me a woman and a couple of drinks I went to bed to get some rest.

In the morning, while I was sitting in the front of the restaurant waiting for the rain to stop, consuming cigarettes and coffee and staring at a goat on the opposite side of the road, inside an abandoned house, I wrote down the following lines:

Like a goat in a box

Chewing and chewing

motionless

Staring at the flickering lights

Chewing the sweet poisons

Forgot hot to breathe, forgot how to listen, forgot how to see

Chewing and chewing

In the world of the somnambulistic chewing goats

Chewing the word of the wise men

Staring at the flickering devices

And the emptiness is broken by the bleating and prattle of chewed words and the howling of the iron beasts

Got to sleep my little matryoshka doll, your dreamless sleep

To rest your jaws.

I cursed the weather and myself for choosing the worst possible time (rainy season) to be at this place and got set for mud-wrestling.

I was moving slowly through mud flooded dirt roads and it was already midday when I reached a wooden bridge over a swollen torrent. While I was waiting after setting the recorder, unease manifested in my mind listening to the shrilling chorus of the insects. I tried to imagine their chorus blending in with the whistling and groaning of the jet engines from huge B52 bombers approaching to empty their deadly cargo.

On the bridge

I continued my ride to Ban Nongboua, a village with a free-standing limestone outcrop nearby. Caves inside this rock had housed hundreds of local villagers and Vietcong troops back then, protecting them from the bombings. I had read that you can hire a local guide in this village, but as I talked to the people they were dismissive and didn’t want to hear anything about this subject. I let it be and went on strolling around the village looking for traces of the past, which were not to oversee.

Scrap metal is a valuable resource and Laotians are very inventive in transforming bombshells to useful objects. The value of the material is also one reason for accidents because many households have a metal detector and people are searching for it. Notwithstanding the above, the sight of bombs turned into crafts, barbecues, containers, traps, stairs, pig troughs showed me that as much as we are capable to destruct, as much we are capable to create.

On my way out of the village, I stopped some children and asked them to show me the way to the cave. They led me to the entrance of the Tham Nam passage which was cutting through the mountain to the cave of the Vietcongs. I had read that it is dangerous to walk through because the cave took a direct hit during the bombings and was in danger of collapsing. I stayed a little at the entrance, recorded and moved on.

Listen to the secret cave

As I continued riding, surrounded by lushly paddy fields and limestone Karsts I could hear controlled explosions in the distance and knew that there were MAG crews cleaning fields nearby also indicated by signs along the road.

I crossed a suspension bridge, entered the village Ban Phanop and parked my bike.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail was passing through it and I was astonished walking along the cobblestone path to find tiny metal objects, scrap, and other remnants of that time. It looked that not much has changed in the last four decades. It also took me a while to understand that all the flooded pools scattered along the landscape were bomb craters. Once again there were a lot of transformed bombshells around, even the frame of a cabin of one of the trucks which were operating on the Trail. I entered the frontward of a Buddhist temple and found the wingtip from a downed Phantom F-4C Jet. The wingtip belonged to a jet that had an interesting story and was the cause of the largest rescue mission during the Vietnam war.

The next village I arrived to was Ban Vangkhon, heavily bombed during the secret war with pools and bomb craters everywhere. I made some recordings on the way at some caves and continued to Ban Senphan, which was not of particular interest. Short after it, I arrived at a point, where I would need to cross the river Nam Ngo with my motorbike on one of the rafts. The rapids were strong and I didn’t dare to risk losing my bike into their waters. That marked the end of my short excursion to the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

I arrived late evening back to the hotel, covered in mud. I washed my bike and myself diligently in a ritual of outer and inner cleaning and left the next morning towards new adventures.

What I have experienced was just a glimpse of the secrets and natural wonders, still hidden in the remote areas between Laos and Vietnam.

Looking back to this day, the impression which I kept was that the most horrendous bombings in the history of mankind have either succeed to erase the beauty and wilderness of this mysterious place nor to break the people of Laos.

I wish one day to come back well prepared with a better motorcycle and some companions for the ultimate adventure into the caves, jungles, and mountains.

Recording of cowbells made out of bomb shells

MAP AND POINTS OF INTEREST

(You can then import the location data and infos to Google Maps or MAPS.ME)